JON’S MOST MEMORABLE:

by Jon Hendershott

Part VI—Men’s Throws & Decathlon.

Shot:

As I have said before many times in this series, a World Record always gives a thrilling, unexpected jolt of excitement to the viewing of any track & field competition. And a WR is memorable, too.

For my most memorable shot performance, I recall immediately being more than 100 yards away from the feat. On May 5, 1973, at a sun-washed but windy San José Invitational, I was trying to keep an eye on the men’s shot competition while I warmed up and stretched before running (I guess that’s what you could have called it) the 120-yard high hurdles. I was strictly a club-level runner, at best, but every once in a while, I got lucky and was included in a hurdles field at a “major” meet in northern California. (And I even competed once at the Mt. SAC Relays in southern California and the West Coast Relays in Fresno—in the bygone dirt-track days of both meets.)

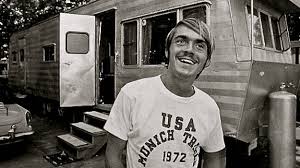

I was standing by the starting line at the north end of San José State’s Bud Winter Field, the winds that sometimes could blow off the southern end of San Francisco Bay whistling down the homestretch. I knew that the men’s shot was underway and that Munich Olympian Al Feuerbach was about to throw.

Al was a big, friendly guy from Kansas who had moved out to San José to train a couple of years earlier. He was 25 at the time and would stop by the Track & Field News offices every so often, to talk track in general and the shot in particular. We staffers all considered Al to be a good friend.

Representing the then-premier U.S. club, the Pacific Coast Club based in Long Beach, California, Al had placed 5th in the Munich Olympics and had had several excellent indoor seasons, including the recently-concluded ’73 campaign.

My attention was split between my own warming up and watching for Al to throw. I, and the several hundred fans watching the meet, were rewarded when his opening effort sailed out to 70’10” (21.59)—then his personal best.

So I would do a few leg stretches, then glance up to see if Al was entering the ring. He was easy to spot, even from a straightaway of the track away, since Al wore a white headband to hold back his blond locks and also a brightly-striped t-shirt under his white PCC jersey.

In round 2 of the throwing, I looked up just as Al crouched at the back of the circle. Then his left leg fired back in the then-predominant O’Brien style of throwing and he powered across the circle, turning at the toeboard and letting the ball go with a loud grunt. Yes, I could even hear his effort 100 yards away.

The shot’s trajectory was rather flat, not high and soaring. But it flew and flew. Clear out to almost the end of the landing area. When it thudded down, the crowd erupted with a roar. Everybody knew it was long.

Indeed it was: no less than a World Record 71’7¼” (21.82), that relegated Randy Matson’s fabled 71’5½” (21.78) to “former record” status. Matson’s ’67 effort had been history’s only 71-footer up to then.

Of course, I was excited as heck to have seen an unexpected record. But the clerk was checking in the hurdlers and I had a reporter’s dilemma: do I run my race, or grab the notebook I had in my shoe bag and run down to the shot area to get some quotes from the new recordman?

Well, you know what I did: I ran over to my bag, being watched by good friend and West Valley Track Club teammate Tom Jordan (the long-time director of the superb Prefontaine Classic Diamond League meet), dug out my notebook and lit out for the shot. Tom recently related that I said to him, “Well, time to go to work.” Indeed it was.

Al was grinning from ear to ear and accepting congratulations from many officials, athletes and fans. Luckily, the throng gathered while officials remeasured the throw, weighed the ball and other official-type duties that stopped the meet for a few minutes. So I was able to get some at-the-moment comments from Al—but then he soon excused himself as he fully intended to keep on throwing. “I feel super!” he smiled. “Don’t make me stop now!”

So I sprinted back up the track—against the wind, I might add—pulled on my spikes as the meet got back on schedule and ran my race. I’m virtually certain I placed 8th and last but I’m not sure I broke 16-seconds, my usual goal for the high hurdles. I like to think that I did since the race had an aiding wind of about 6mph behind it.

But after I finished, I pulled on my sweat clothes and rushed down to sit at the end of the shot landing area to watch the rest of the throwing and take notes for a magazine story. We would wrap up our next edition just two days later, so I had to get as much material for a report as I could.

And Al gave everyone plenty to watch: he took all six of his throws (Nos. 3 through 6 measured 69’5¾”/21.175, 69’1”/21.055, 69’6”/21.18 and 70’7¼”/21.52) and averaged a sparkling 70’2¼” (21.39).

Afterward, Al said, “It really wasn’t a phenomenal throw. But I did get behind the shot well and my motion was more continuous through the middle of the put.” He also a bit reluctantly admitted, “Now I can look more realistically at 22-meters [72’2¼”].”

Yet in the mercurial way that our sport can work, that record throw turned out to be the longest of Al’s career. But he nonetheless compiled a stellar résumé, taking 4th in the ’76 Montréal Olympics, making the ’80 Games team-that-didn’t-go and World Ranking 9 years in a row (No. 1s in ’73 and ’74) and U.S. Ranking 13 straight seasons (No. 1s in ’73 through ’76, plus ’78).

As much as I would have loved to see Al win an Olympic medal, I feel so fortunate that I did get to see his longest throw ever—and at the time, the longest in history. That is an unbeatable thrill.Al Feuerbach WR ( It's only 4 sec. long. Watch closely. ed.)

Discus:![]() |

| Mac Wilkins |

Several years after moving to San José to train, Al Feuerbach got a roommate with a similar drive to excel in throwing. Mac Wilkins was two years younger than Al and had been a blooming javelin talent at Oregon, reaching a PR of 257’4” (78.44) in 1970. But then an elbow injury ended his spear-throwing days. So he turned to the shot and discus, especially the plate. The discus would never be the same again.

Especially after May 1, 1976. On that day at the San José Invitational, and three years after Feuerbach’s shot record at the same meet, Wilkins was to face arch-rival and another localite, John Powell. The San José State grad, an officer in the SJ Police Department, had been a leading U.S. discusman since the early 1970s and had placed 4th in the ’72 Munich Olympics.

There never was any love lost between the two athletes: the bearded, fire-in-his-eyes Wilkins and the laconic Powell. But both were highly-driven throwers, determined to be the best in the world—which meant being the best in San José first.

Powell started the ’76 Montréal Olympic season as the World Record holder after flinging the platter 226’8” (69.08) in 1975. Wilkins got in his first volley at the ’76 Mt. SAC Relays in late April when he reached a record 227’0” (69.18). So the stage was set for their meeting in San José on May Day of the U.S.’s Bicentennial Year.

Wilkins didn’t give anyone else a chance on a day when the winds which often blew at Bud Winter Field came from the helpful-to-the-disc right quarter. The breezes would pick up the outer right edge of the platter and turn it into a Frisbee looking for more lift—and distance.

So Wilkins whirled his first toss out to no less than 229’0” (69.80) to lengthen his WR by exactly two-feet. As the fiercely-concentrating Wilkins walked back toward the circle after retrieving his platter, he called to Powell, who was about to enter the ring for his first effort, “Put it away, John. It’s all over.”

Ever the gamer, Powell nonetheless gave it his best and eventually got out to a longest-for-the-day of 220’4” (67.16). But Wilkins was far from over as his second toss sailed out to 230’5” (70.24)—history’s first throw ever to exceed both 70-meters (229’8”) and 230-feet.

![]() |

| Powell and Wilkins |

And Wilkins didn’t turn down his intensity: on his third heave, the disc sliced down at 232’6” (70.86). With three throws, Wilkins had extended the World Record by more than 5-feet.

Not content to stop throwing, Wilkins took his full allotment of six, reaching 219’9” (66.98), 223’1” (68.00) and 218’6” (66.58) on throws 4 through 6. That series averaged out to 225’5” (68.74), a mark that only Wilkins and Powell had ever surpassed even once before that day.

As if to underscore his dominance, Wilkins also became the first thrower ever to hurl three WRs in one day. Several others had hit a pair of records in the same meet, but never three.

Wilkins would go on to win the Montréal Olympic title (with Powell 3rd) and rank No. 1 in the world for ’76. He would rate globally a dozen times during his career, make three more Olympic teams, win the ’84 Games silver medal (Powell again taking 3rd) and place 5th in Seoul ’88.

He was nicknamed “Multiple Mac” for his versatility in throwing: he got his disc best of 232’10” (70.98) in ’80 and also put the shot a longest of 69’1¼” indoors (21.06) in ’77 and whirled the hammer 208’10” (63.65) in ’77 to go along with his javelin best of 257’4” (78.43) in ’70.

Multiple talent, indeed, but never more stunning or dominant than that sunny and windy day in San José. I was so lucky to be there to see Mac make history—three times in a row.Wilkins v. Powell (This is some very amateur video of that Wilkins-Powell duel. A re-enactment might be better quality but it wouldn't be real. Would you rather be in boat with Washington crossing the Delaware or watching it on HBO? ed.)

Hammer:

Mac Wilkins and Al Feuerbach also figured in my most notable hammer memory. I had gotten to be a true fan of the event thanks to the announcing that T&FN staffers did at local Bay Area meets, starting in the late-’70s. The meets often were staged at San José City College under the guidance of ultra-eager head coach Bert Bonanno.

But since the SJCC stadium was just a junior-college football set-up, the long throws couldn’t be held inside the stadium. The discus and hammer were relegated to an adjacent throwing field. Someone was needed to announce the long throws on the outer field and I volunteered.

So over the next decade or so, I got to know many of the long throwers, from Mac, John Powell, Ken Stadel and Connie Price-Smith in the discus, to Jud Logan, Lance Deal and Ken Flax in the hammer.

My hammer memory centers more on what happened after the throwing than during it. The 1978 US-USSR dual meet was staged in Berkeley, at Cal’s Edwards Stadium. Among the notable athletes on the Soviet men’s team were two youngsters: emerging high jumper Vladimir Yashchenko (or properly “Volodymyr” in his native Ukraine) had been the World Record holder for just over a year, even though he was just 19 years old even then.

The other was hammer thrower Yuriy Syedikh (or “Sedykh” as the IAAF lists him). He came to the Berkeley dual meet as the Olympic champion, having won in Montréal two years earlier at barely age 21. He had earned the first of his eight career No. 1 World Rankings after his Games triumph—his eighth would come in 1991 after a World Championships victory in Tokyo at age 36.

Syedikh had no problem winning the U.S. dual meet, tossing the ball-and-wire 246’8” (75.16). Then came the memorable day after. The meet had ended on Saturday, July 8. The next day was a sunny Sunday and the visiting athletes were given the day off before leaving for home on the Monday.

Several of the Russian throwers wanted to get in a workout before the long return journey. So Mac Wilkins and Al Feuerbach arranged for a group to put in a training session at San José State’s Bud Winter Field. Then the two American icons invited everyone to their house in the foothills of the Santa Cruz mountains west of San José. I was lucky enough to also be invited.

Also along was my friend Janis Donis, a Latvian by birth who had been a world-class javelinist for the USSR team in the early ’70s before being penalized by Soviet authorities for marrying an American. ![]() |

| Janis Donis |

Janis eventually was allowed to join his wife and daughter in America and had come north to the Berkeley meet from his home in Los Angeles to renew old friendships with some Soviet throwers.

There were seven or eight throwers in the group and—most notably as I recall—no officials, or KGB agents. (We had taken to calling such minders “the lookers” after having them pointed out during the ’71 Russian visit to Berkeley. The lookers were the guys in the dark or mirrored sunglasses that they never removed and, even in the 90-degree heat of a California summer, they wore all-black, including turtleneck sweaters and leather jackets—the archetype of a James Bond-genre Russian secret agent.)

Among the Russian throwers was blond shot putter Yevgeniy Mironov, the Montréal silver medalist who I had met two years earlier when he competed in San Francisco with a small group of touring USSR athletes (including double ’72 sprint winner Valeriy Borzov). Mironov was a bespectacled fellow who always seemed to be smiling.

Janis Donins spent a lot of time talking with Soviet javelinist Nikolay Grebnyev, who would go on to place 2nd in the late-August European Championships in Prague.

The get-together at Mac & Al’s mountain home—which featured a regulation shot throwing area and a fully-equipped weight room—offered the athletes and guests a chance to kick back and relax in the fresh mountain air and California sunshine. The hosts provided snacks and soft drinks for everyone and there even was a large watermelon—which all of the Russians claimed they had never seen before, much less tasted. But they gamely tried the juicy red fruit—and love it to a man.

Then of course, these being Russians, a bottle of vodka was brought out and toasts were made all-around. A good time was had by all—all, that is, except Yuriy Syedikh. Someone eventually noticed the hammer thrower’s absence and asked where he was. I think it was Mironov who jerked his thumb toward the weight room and replied, “Prague is coming.”![]() |

| Syedikh |

Yes, Syedikh had spent more than two hours doing a full lifting workout—the day after winning the dual meet competition and after a full throwing workout earlier that Sunday. Everyone else relaxed, but not Syedikh. Very late in the mountain gathering, Syedikh finally made an appearance, sweat-soaked, as everyone was preparing to leave.

Yet he later reaped the final reward by claiming the first of his three consecutive European titles in Prague. After taking the ’78 win, Syedikh defended his Olympic title in Moscow in ’80, then repeated as continental champion in both ’82 and ’86. At the latter, he produced a stunning World Record of 284’7” (86.74) that bettered his own 284’4” (86.66) thrown earlier in the ’86 season. At the Europeans, Syedikh’s series also included throws of 284’4” (86.68) and 284’2” (86.62)—merely three of the four-longest throws in hammer history, all in the same meet.

Goes to show what his work-first concentration on training and preparing did for Syedikh, both on that day in the Santa Cruz mountains and throughout his career. And I don’t think he got any watermelon at Mac & Al’s house, either.

Javelin:

My two most memorable javelin throws both were World Records. Few sights in our sport in general can top the beautiful arc of a spear toss as it flies out toward the landing area. When such a throw is a record, it usually has the watching crowd roaring in excitement as the spear lands beyond whatever color of a chalk line marks the WR distance on the green grass.

The first such throw for me came at the ’76 Montréal Olympics. I shared T&FN’s media section seats with the magazine’s co-founder and editor Bert Nelson, plus editorial department colleague Garry Hill and longtime correspondent Don Steffens.

Bert was a reserved, taciturn man, but with a lively sense of humor when he wanted to let it out. As we watched the javelinists warm up on that July 26 at the ’76 Games, Bert turned to us as said with his sly grin, “Let’s have a pool for a quarter: how many javelins will land between the Olympic Record line and the World Record line?”

West Germany’s Klaus Wolfermann had set the Games best four years earlier with his 296’10” (90.48) winner in Munich, while the global mark stood at Wolfermann’s 308’8” (94.08) a year later. (These marks were reached with the old-specification javelin. In ’86, the implement’s center of gravity was shifted forward due to safety concerns, especially following the gargantuan 343’10” (104.80) thrown in ’84 by East German Uwe Hohn. That is still the longest throw ever with any specification of javelin.)

I don’t recall the numbers we produced for Bert’s pool. But playing such games at meets always meant we would watch the concerned event with extra care. In Montréal, it was a good thing we paid attention right from the opening throw.

Leading off the Olympic competition was Hungary’s Miklós Németh. The 29-year-old had World Ranked as far back as 1966 at age 19 and came from a true Olympic pedigree: his father Imre won the ’48 Games hammer title. Yet Miklós never had won a major championship medal, let alone of the golden variety.![]() |

| Miklos Nemeth |

Németh reached 292’11” (89.28) the day before, second-longest in qualifying behind the 294’6” (89.76) by Finn Seppo Hovinen. So the Hungarian certainly was ready for something big. And did he ever produce a monster.

He came down the runway for the event’s opening effort, not looking particularly fast but definitely smooth. Németh reared back and let the spear go in a rather flat trajectory. But boy, did it fly…and fly…and fly.

All the way past the Olympic Record line, then the gap to the WR stripe and then well beyond that global mark. The crowd roared after the implement speared into the turf of Stade Olympique.

Németh himself watched the flight he had generated, then turned and walked a few steps back up the approach. Then he turned to look again—and after a few more steps, he turned to look once more. Then he leaped into the air, his legs tucked under him and both arms thrust over his head.

He knew it as a big one and in a few moments, the swiveling electronic scoreboard let the world know just how far the throw had gone: 94.58, a World Record 313’7”.

Just like that, the competition was over. Hannu Siitonen, Finland’s other big hope, followed the record setter as the second thrower and reached a still-excellent 288’5” (87.92). Eventual bronze medalist Gheorghe Megelea of Romania also got his longest of 285’1” (87.16) on his first effort.

Of course, nobody else could approach Németh’s opening bomb, not even Németh himself. He passed his second and third opportunities, then took his three remaining throws. His sixth measured 284’11” (86.84), which still would have placed him 3rd.

But Németh had that golden opener that settled everything. The record heave also squelched Bert’s pool, since no one got any throw between the WR and OR lines. Németh went over the former and no one exceeded the latter. Bert dutifully returned the invested quarters to all the pool players—and as I remember, with a smile.

Nemeth's Throw at Montreal (Hope you speak Hungarian ed.)\

My other memorable javelin toss was an even more unlooked-for global best than Németh’s. That big throw came nearly seven years later, on May 5, 1983, at the Pepsi Invitational staged at UCLA’s Drake Stadium.

Prime among the entries was American Record holder Bob Roggy, who had hit 314’4” (95.80) the previous summer in Germany and who had been the No. 1 U.S. Ranker for four of the past five seasons.

I also was especially interested to see young American Tom Petranoff, who had emerged nationally in 1980 and had rated as No. 2 American in ’82 behind Roggy. Petranoff had only been throwing a few years; he first tried the javelin as a junior college baseball pitcher after watching his track teammates throw the spear. “I can do that,” he thought and he soon was out-throwing the javelin specialists. Yet he still was learning the event. At Pepsi, he showed that he already knew plenty.

To digress for a moment: as I have explained in some previous chapters, the T&FN“PR Rule” stipulated (and still does) that you have to see all of a record performance, start to finish, to claim it as a “PR seen.” So it was at Pepsi. It was a warm, sunny Los Angeles day and the javelin was the first event staged at the meet. Fans still were filing into Drake Stadium, coming up stairs from trackside to find their seats.![]() |

| Tom Petranoff |

This being southern California, there were more than a few very attractive young women among the fans. And the common “uniform” seemed to be very-short shorts and revealing halter tops. I was already in my press seat as the javelin began, but I noted that several of my officemates were watching the entrance of one especially attractive young lady—who was not shy about showing off her, ahem, “best” qualities.

But then I noticed that Petranoff was at the back of the javelin runway, ready for his second throw. His first had traveled 274’9” (83.74). So, being that I was going to report on the meet for T&FN, I zeroed in on him. Tom’s loping approach led up to a whipping delivery, punctuated by his mighty yell.

And the spear simply exploded out of his hand—and took off like a missle. The silver implement reached that beautiful, arcing apex and even though it still was coming down, it kept sailing farther and farther out into the landing area. Then it nosed down—well beyond a row of yellow balloons that marked the global best of 317’4” (96.72). Another Hungarian, Ferenc Paragi, had reached that mark in 1980 to better Németh’s Montréal record.

The crowd erupted and the excitable Petranoff threw his arms above his head. He knew it was a good one—and once the long tape told its tale, so did the world: 327’2” (99.72), nearly 10-feet beyond the old record and the closest any thrower had ever come to the mythical 100-meter mark of 328’1.”

The officials then had to take the time to verify the record effort, as harried photographers crowded around Petranoff. He passed his third and fourth throws, but finally gave in to the pleading cameramen to throw again—so they could at least get still shots and footage of him throwing, since they had missed the actual record toss.

So Tom complied and put his fifth try out to 281’10” (85.90) before passing No. 6. Mike Barnett from nearby Azusa Pacific ended up 2nd with a still-respectable 283’4” (86.36), with Roggy 3rd at 274’7” (83.70).

After the jav competiton ended, I talked with the still somewhat dazed Petranoff and I also snagged one of the yellow balloons that marked the old WR line as a souvenir. Then I approached my office mates and said something like, “Well, what did you think of that monster? The throw, I mean.” To a man, they owned up that their eyes were diverted elsewhere and so they had missed seeing the entire record throw.

I knew they wouldn’t have done less, but felt somewhat sorry for them that they had missed one of those bolts-out-of-the-blue moments that make our sport as great as it never ceases to be.Tom Petranoff video

Decathlon:

I can’t say when I started liking the decathlon; perhaps in the early ’70s when I met a decathlete and who kept urging me to try one. I eventually did, even though I was totally self-“coached” and couldn’t high jump, vault or throw the discus even if my life had depended on them.

I eventually got up to a PR of 5193 points in 1973, in the last formal competition I ever did. My overall total would have put me only 465 points ahead of my most memorable 10-eventer’s first-day score.![]() |

| Ashton Eaton |

That’s because Ashton Eaton totaled 4728 after just the first 5 events at the 2012 Olympic Trials. Schizophrenic weather in Eugene exposed the decathletes to sun, wind, rain, cold and heat over their two days of competing, already trying enough by the very nature of the decathlon.

My two most memorable moments in the competition came at the end of each day. Day 1 had been the wet and cold session. As Eaton and ’08 Trials winner Trey Hardee stood at their blocks to run the 400, the skies opened up in a torrential downpour. The athletes might as well have run their lap inside their shower at home. It rained that hard.

Yet Eaton managed a 46.70 to cap his 4728 score after 5 events. The second day was sunnier and warmer. By the time Eaton had vaulted a then-PR 17’4½” (5.30), he was 132 points ahead of the pace of Czech Roman Sebrle during his 9026 World Record 11 years earlier. Up to then, it was history’s only total above the magic 9000-point level.

A 193’1” (58.87) javelin toss by Eaton was his longest ever in a decathlon at that time, but he had fallen 39 points behind Sebrle. Yet the numbers-crunching fans still were thinking of a record—and so was Eaton’s coach Harry Marra. A former decathlete himself, Marra brought both boundless enthusiasm and deep knowledge to his coaching of 10-eventers.

I was especially happy to see Marra working with an ultra-elite athlete like Eaton as I had known Harry for more than two decades. It felt good to see his genuineness as a person and a coach getting the recognition he richly deserved.

Harry told me the story later than even before the javelin, he and Ashton had talked under the Hayward Field stands. Eaton, as eager as his coach, figured what he would have to score in the final two events to better Dan O’Brien’s 8891 American Record, set back in ’92. Harra just replied, “No, Ash, the World Record.” Harry said Ashton just replied, “Oh, okay.”

Eaton related that just before the event-concluding 1500, many of his compatriots (all 16 surviving competitors would run in a single 1500 race) approached him and wished him good luck. No rah-rah talks; just best wishes for a good run.

Renowned decathlon announcer Frank Zarnowski set up the 1500 beautifully, saying it was for sure a race for the World and American Records, but as much for the University of Oregon, the city of Eugene, the state of Oregon and the United States. The 21,795 fans in the stands roared at that.

Everyone knew that Eaton had to run 4:16.23 to better Sebrle’s record. He didn’t go out with ace deca-1500 runners Joe Detmer and Curtis Beach, but Ashton stayed in the front third of the pack. At the bell to start the final 400, he was about 2-seconds behind Sebrle’s pace. But Eaton showed his guts and grit as he worked hard over the final circuit. Detmer and Beach moved away from the inside lane as they entered the homestretch, with Eaton gaining and the crowd absolutely roaring.

In class moves of true sportsmanship, first Detmer slowed to cheer on Eaton and then Beach—with maybe 30-meters to run— slowed even more to wave Eaton into the lead and cross the line as both the race winner and the new World Record setter and U.S. recordman with his 9039 total.

Eaton grasped his head in joy and emotion as he finished and moments later was surrounded in tearful hugs by mom Ros and his now-wife, heptathlete Brianne Theisen.![]() |

| Harry Marra and Ashton Eaton after the WR |

Later that summer, Eaton would win the London Olympic title ahead of Hardee. Then at the’15 World Championships in Beijing, Eaton would boost his own mark to 9045 points. And in ’16, he would defend both his Trials title in Eugene and his Olympic crown in Rio before he and Brianne announced their retirements early in ’17.

After his first record, Eaton said, “I think that one reason the decathlon is so appealing when you actually do one is that it’s like an entire lifetime in two days. You have the ups and downs, the good and bad, the comebacks. It all happens in two days. Everybody loves life and that’s why we love the decathlon.”

![]() |

| Harry Marra and author Jon Hendershott |

Nice article by Jon. Those guys from Track and Field News loved track and knew every event and all the competitors, times and distances. The way they can think in meters still amazes me. I'm a yards and feet guy when it comes to field events.

I stayed in contact with Jim Dunaway until he passed last year and was always amazed at how much he knew and loved our sport.

John Perry

(Next: Women’s sprints & hurdles.)